Time for Thomas

In our study of time, we compared

four leading theories: Presentism, Eternalism, Growing Block Theory, and

Branching Tree Theory. None of these theories are complete. None are cohesive.

To make progress, we extract a metaphysics of time from the work of Thomas

Aquinas, principally the Summa Theologica.[1]

The sections that follow demonstrate a comprehensive and cohesive theory that is far

superior to modern approaches.

Experiencing the Present. A Thomistic theory of time

provides a better solution than Presentism. Rather than grounding time in the

fleeting present of subjective human experience, Aquinas grounds time in God’s

unchanging eternity (ST I, 10.2; ST I, 10.1).[2] God does not experience

time through movement; God is wholly present. Past, present, and future are the

same (simultaneous) to him. For humans, the “now” of time moves, but for God,

this “now” stands still.[3] This treatment agrees with

Augustine.[4] Leftow says “whatever

exists necessarily is intrinsically timeless;” and “God exists necessarily.”[5]

Astrophysicist Hugh Ross[6] uses the analogy of

flatlanders to describe God’s transcendence of time. If life is confined to

planar surface, then God has the superior view from the third dimension,

engaging all time and (flat) space at once. Page[7] observes similarly that

Anselm’s view of eternity is like a super-temporal dimension that contains time

and temporal entities.

God timelessness is not static. He

is a living Being.[8]

Weinandy characterizes the Trinity as three persons fully giving themselves in

love to the other—perichoretic subsistent relations, fully in act.[9] God extends the gift of

life to his time-bound creation.

Contemplation. Aquinas further asserts that the contemplative life

helps us understand God’s eternal presentness. This shared “now,” provides the

means by which humans—soul-formed bodies (ST I, 75-76)—can know God. The

contemplative life lovingly gazes on God’s truth, goodness, and beauty.[10] Accordingly, the quietude

of contemplation experiences God’s presence (or ever present-ness). Temporal

concerns fade and the motion of time slows in our mind as we meditate on God

and his divine rest.

Succession. Aquinas recognizes the experience of time in

succession. This too helps us learn more about God. “As we attain to the

knowledge of simple things by way of compound things, so must we reach to the

knowledge of eternity by means of time, which is nothing but the numbering of

movement by ‘before’ and ‘after.’ For since succession occurs in every movement,

and one part comes after another, the fact that we reckon before and after in

movement, makes us apprehend time.” We experience time in two ways: “time

itself, which is successive; and the ‘now’ of time, which is imperfect.” “Time

is the numbering of movement (ST I, 10.1).”

According to Aquinas’s time is

grounded in God’s eternity. The creation of time provides the means for man to

know God, the end (goal) of all human endeavor.

Time’s Structure. Aquinas provides a comprehensive

description of time’s order. Time has a beginning, an ordered structure, and an

end. The experience of time enables humans to learn and grow.

Time’s beginning. Aquinas says: “Things are said to

be created in the beginning of time, not as if the beginning of time were a

measure of creation, but because together with time heaven and earth were

created (ST I, 46.3).” “That the

world began to exist is an object of faith, but not of demonstration or science

(ST I, 46.2).” There are two reasons for this. First, quoting Jerome,

Aquinas states "‘God is the only one who has no beginning.’ Now whatever

has a beginning, is not eternal. Therefore, God is the only one eternal (ST

I, 10.3).” Second, God creates the universe voluntarily, not of necessity (ST

I, 19.3). Therefore, reasoning from cause to effect may be inconclusive.

But, philosopher of science Stephen Meyer argues that key scientific findings

in the 20th century make a compelling case for a beginning to the

universe and therefore a cause behind this beginning.[11]

Time’s order. In his teleological argument Aquinas argues: “Now

whatever lacks intelligence cannot move towards an end, unless it be directed

by some being endowed with knowledge and intelligence…Therefore, some

intelligent being exists by whom all natural things are directed to their end. (ST

I, 2.3).” Meyer supports this observation by noting the extreme fine-tuning

of the universe. This includes the incomprehensible fine-tuning of the

universe’s initial conditions, to 1 part in 1010^123, and this

according to the Nobel-Prize-winning physicist Sir Roger Penrose.[12]

Time’s end. “Since the beginning of all things

is something outside the universe, namely, God…we must conclude that the end of

all things is some extrinsic good…The end of the whole universe must be a good

outside the universe (ST I, 103.2).” Aquinas understands this to mean

that humans have an eternal future participating in the divine life. "God

was made man, that man might be made God (Augustine quoted in ST III,

1.2).”[13]

Parker and Jeynes[14] (Parker, 2023) develop a

model that demonstrates that the 2nd Law of Thermodynamics is a fundamental (rather than

emergent) property of the universe. Using a complex (2D) time approach, in

which the real part of time is irreversible and the imaginary part of time is

reversible, they show that a system’s Hamiltonian and its entropy production

are Wick-rotated complex conjugates of each other. Time’s arrow is built into

the design of the universe.[15]

Time’s progression. In contrast with the B-series that only records

events, time’s progression has a purpose. For unlike God, who knows things

“altogether at once” (ST I, 14.7), human learning takes time.[16] This is movement (in

time) from ignorance to knowledge. Learning prepares us for the future.[17] Virtuous habits measure

this progress.[18]

This again matches Meyer. His third

argument for a theistic origin to the universe is life’s DNA code.[19] When bacteria divide,

they pass on their DNA to their progeny. Replication includes error checking.

Bacteria adapt to changes in the environment, and pass on what they learn to

the next generation. Learning is a design feature of the universe. Life is digital.

A-theory anchors time to the

present. This works for Aquinas because God is always present. The present is

indeed privileged. B-theory anchors time to physics. The spacetime universe had

a beginning. Time is part of the geometry of the universe. Aquinas takes this

further. Time has a beginning and an end. Time is structured so life can learn.

The book of life keeps a permanent record (Rev. 20:15).

Progress in Time. In the analogia entis (analogy

of being), Aquinas offers a better approach than the Growing Block Theory. The

universe is ordered to God’s end, and human learning has a goal—the beatific

vision. Man is made in God’s image. God shows himself through the incarnation,

and we learn by analogy. God shapes the world for man and God shapes man to

return to God. According to Thomas, and following Aristotle, man is neither

like God (univocally), nor unlike God (equivocally), but is apprehended in similarity

(analogically).[20]

God makes himself known to man through both nature and grace.[21] Analogy is another old

idea. Four hundred years before Moses, the Middle Bronze Age herdsman Job

sought an intermediary between himself and God (Job 9:33).

Guided by the writings of the

German-Polish Jesuit philosopher Erich Przywara (1889-1972), John Betz[22] (Betz, 2023) unfolds the

analogy of being, as part of his analogical metaphysics. For Betz (and

Przywara) analogy provides the means to connect human and divine. Beholding God

in the flesh provides our example (John 1:14). Through grace, God conforms us

to the image of his Son. Transformation occurs incrementally, in time,

which is the perfecting goal of analogy (1 John 3:2). Learning through analogy

and time progresses to the achievement of God’s good end, not only for

individuals but for the church through the ages.[23]

Aquinas gains important support

from science. There is an optimizing principle in biology. Organisms optimize

their performance in search of physical limits. Biophysicist William Bialek

(Bialek, 2012) documents optimal performance in the single photon counting in

eyes, echolocation in bats, fruit fly embryo development, and cellular

information processing (Tkačik, 2016). Living systems seek the best the

Lawgiver has for them. It follows (by analogy) that humans can also aim for

best performance, whether in mastering the violin, understanding the secrets of

the atom, or in becoming more like Christ.

The unfolding (ascent) of the

universe with time results in the formation of galaxies that host stars that

accrete planets that can host life. God causes life to grow until the planet is

ready for human life. The universe will eventually wind down (descent) but

before it does, God descends (condescends) into the universe in the incarnation

(ST III, 34.1). His resurrection (ascent) leads the way, and humans have

the opportunity to ascend to God. This single cycle of death and

resurrection repeats (in analogy) in the evening and morning of the Hebrew day

and the yearly cycle of seasons.[24] Time is cyclical.[25]

An expanding universe provide

capacity for complexity. God uses this capacity to originate life, visit

humanity, and accomplish his good ends. Aquinas not only describes the

opportunity for learning within time, but the goal of this learning, which is

the ideal of Christlikeness. We learn by analogy. In modern terms, time is an

interface.

Free Will in Time. Aquinas provides a clearer

understanding of time and its use by human agents than the Branching Time

Theory. First, allaying Prior, Aquinas acknowledges human free will (and moral

responsibility). However, the work of free agents is only good if it serves a

greater good.[26]

God willingly creates the world to achieve his good end. By his authority,

kings (and other subordinate authorities) exercise their free will to good

ends. However, man needs help in accomplishing God’s good works.

Aquinas gains support from science

and engineering. The Belief, Desire, and Intention (BDI) framework, with

heritage in the tensed logic of Prior, is an important artificial intelligence

(AI) tool for rational (intelligent) agents that mimic human reasoning and

decision-making.[27]

But in a nod to Aquinas, the robotic systems work to the particular ends of

their human designers. Autonomous agents serve proximate ends, but lack the

wisdom and foresight of their designers. Similarly, God’s good ends apply to

the right working of kingdoms and the ordering of families.

Significantly, God is in full

knowledge of possible worlds (counterfactuals). These he knows at once in the

simultaneity of his ever-presentness.[28] This aligns with Lewis

and fixed manifolds associated with possible worlds. This raises the question

of predestination. Aquinas acknowledges original sin (ST I-II, 82) and distinguishes

between operating and co-operating grace.[29] We need God working in

us for salvation (operating grace) and with us for godly living

(co-operating grace) (ST I-II, 111.2). Freewill actions submit to the

divine authority that moves heaven and earth and apply to the building of the

New Jerusalem. Augustine (Augustine, Exp. Ps. 122) argues that preaching

the gospel and caring for the poor add stones to the foundation of the City of

God.

In robotics and in human

experience, solutions to difficult problems benefit from outside expertise.

This does not obviate autonomous (algorithmic) decision making or human

(conscious) free will, but without receiving a helping hand, it may not be

possible to solve a specific problem or to “level up” to a new capability. By

analogy, man needs God’s grace. Grace provides the only opportunity for

soul-formed bodies to enter into the blessing God envisions. God made us so we

can know this freedom.

Summary of Thomistic Metaphysics of

Time. The table

contrasts the scholastic system with the weaker and incomplete modern

approaches. This is a coherent and comprehensive approach.

Thomas Aquinas provides a

philosophy of time grounded in God’s eternity. Time has two aspects: its

succession from before to after, and its presence, the “now” of time. God’s

creation of the universe marks the beginning of time. The universe is ordered

to its end, and time records this progress. Man (soul-formed body) can know God

both through nature and the incarnation. This knowledge is analogical. Knowing

God takes time. Learning progresses discursively, through contemplation, and in

the development of virtuous habits, corresponding to the movement in time from

ignorance to knowledge (succession), rest that comes from gazing on God’s love

(and his ever-presence), and practical experiences of virtuous living. Humans

are moral agents; their free actions can accomplish great good. Man needs God’s

help for salvation and for godly living. God knows all the possibilities at

once. The final end, and the corresponding end of time, is the beatification of

the saints in body and soul, experiencing delight in God’s presence, love, and

goodness.

There is room for further exploration of this theory. Additional study could seek to understand not only what time is (a single cycle of God’s complete action, and an interface for knowing God), but what time represents. Just as physical light represents the divine light of God’s glory (ST I, 12.5; Conf., xxxiii, 51-53), physical time may represent a divine vitality. God is unmoved by the time he creates, but he is also a living being. He is always acting (relating) in the present, in fulfillment of his wise plans.

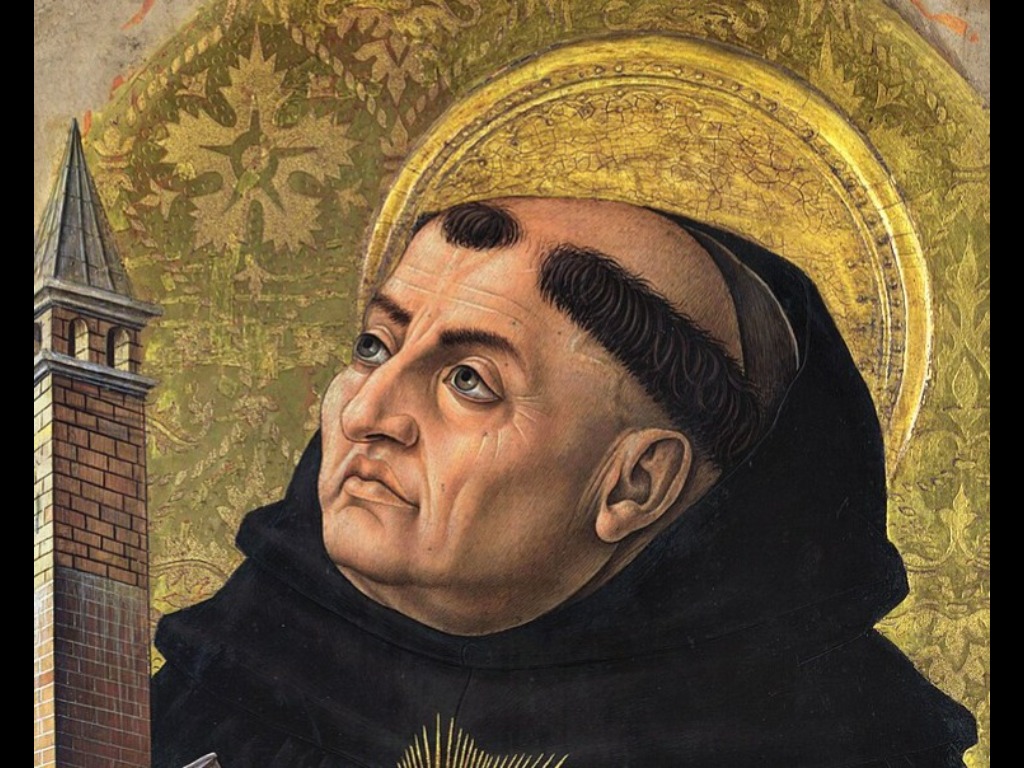

Image: Public Domain.

[1] Thomas Aquinas, Summa

Theologica, trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province (Grand Rapids,

MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library, n.d.), https://www.ccel.org/ccel/a/aquinas/summa/cache/summa.pdf.

[2] “The idea of eternity follows

immutability, as the idea of time follows movement…Hence, as God is supremely

immutable, it supremely belongs to Him to be eternal. Nor is He eternal only;

but He is His own eternity; whereas, no other being is its own duration, as no

other is its own being (ST I, 10.2).” “Eternity is known from two

sources: first, because what is eternal is interminable—that is, has no

beginning nor end…secondly, because eternity has no succession, being

simultaneously whole (ST I, 10.1).”

[3] “We apprehend the flow of the ‘now,’

so the apprehension of eternity is caused in us by our apprehending the ‘now’

standing still (ST I, 10.2).”

[4] “It is not in time that you

precede times. Otherwise, you would not precede all times. In the sublimity of

an eternity which is always present, you are before all things past and

transcend all things future, because they are still to come, and when they have

come, they are past…Your ‘years’ neither go nor come. Ours come and go so that

all may come in succession…Your ‘years’ are one ‘day’ (Ps 90:4, 2 Pet 3:8), and

your ‘day’ is not any and every day but Today, because your Today does not

yield to a tomorrow, nor did it follow on a yesterday. Your Today is

eternity…You created all times and you exist before all times. Nor was there

any time when time did not exist (Confessions, XI, xii, 16).”

[5] Brian Leftow, Time and Eternity

(Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991), 270.

[6] Hugh Ross, The Creator and the

Cosmos: How the Greatest Scientific Discoveries of the Century Reveal God, 3rd

expanded ed. (Colorado Springs: NavPress, 2001), 113.

[7] Ben Page, “Timelessness à la

Leftow,” TheoLogica: An International Journal for Philosophy of Religion and

Philosophical Theology 9, no. 1 (March 19, 2024), https://doi.org/10.14428/thl.v9i1.80543, accessed April 2, 2025.

[8] “What is truly eternal, is not

only being, but also living (ST I, 10.1).” “'Eternity is the

simultaneous and complete possession of infinite [limitless] life (Boethius,

1902, V, vi).”

[9] Thomas G. Weinandy, “The Immutable

and Impassible Trinity, Part 2,” in On Classic Trinitarianism, ed.

Matthew Barrett (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2024), 359.

[10] “That

which belongs principally to the contemplative life is the contemplation of the

divine truth, because this contemplation is the end of the whole human life.

Hence Augustine says (De Trin. i, 8) that ‘the contemplation of God is

promised us as being the goal of all our actions and the everlasting perfection

of our joys.’ This contemplation will be perfect in the life to come, when we

shall see God face to face (ST II-II, 180.4).” “External bodily

movements are opposed to the quiet of contemplation, which consists in rest

from outward occupations: but the movements of intellectual operations belong

to the quiet of contemplation (ST II-II, 180.6).”

[11] Nobel prize

winner Arno Penzias, who with Robert Wilson detected the Cosmic Microwave

Background signal (the afterglow of the Big Bang) says “the best data we have

are exactly what I would have predicted, had I nothing to go on but the first

five books of Moses, the Psalms, the Bible as a whole (quoted in Meyer, 2021,

243).” The observations of science confirm what Aquinas could only reason to be

true.

[12] Another example

of fine tuning is the triple-alpha process that forms carbon in stellar

nucleosynthesis. This discovery caused astronomer Fred Hoyle to posit that a

super-intellect that had “monkeyed with physics (Meyer, 2021, 139, 148-151).”

[13] Man does not become God, but in the

future mankind participates in the divine nature (ST I-II, 112.1).

[14] M. C. Parker and C. Jeynes,

“Relating a System’s Hamiltonian to Its Entropy Production Using a Complex Time

Approach,” Entropy 25, no. 4 (2023): 629, https://doi.org/10.3390/e25040629.

[15] This work is

unconventional and not yet widely accepted; but it is worth following.

[16] “In our knowledge there is a

twofold discursion: one is according to succession only, as when we have

actually understood anything, we turn ourselves to understand something else;

while the other mode of discursion is according to causality, as when through

principles we arrive at the knowledge of conclusions (ST I, 14.7).” In

fact, God brings time to us, allowing us

to see light from galaxies billions of light years away—a grander disclosure

than the Psalmist knew (Ps 19:1-4)!

[17] “Memory of the

past is necessary in order to take good counsel for the future (ST II-II,

49.1).”

[18] “The rational powers, which are

proper to man, are not determinate to one particular action, but are inclined

indifferently to many: and they are determinate to acts by means of habits…Therefore

human virtues are habits (ST I-II, 55.1).” “The act of virtue is nothing

else than the good use of free-will (ST I-II, 55.1).”

[19] Each of the trillion cells in an

adult human body has approximately 3 billion base pairs of DNA. The nucleotide

bases form a 4-bit code. Even the simplest single-cell organisms (bacteria)

have this code (Meyer, 2021, Ch. 9-10).

[20] “For in analogies the idea is not,

as it is in univocals, one and the same, yet it is not totally diverse as in

equivocals; but…signifies various proportions to some one thing (ST I, 13.5).”

[21] “It would seem

most fitting that by visible things the invisible things of God should be made

known; for to this end was the whole world made, as is clear from the word of

the Apostle (Rom. 1:20): "For the invisible things of God…are clearly

seen, being understood by the things that are made." But, as Damascene

says (De Fide Orth. iii, 1), by the mystery of the Incarnation are made

known at once the goodness, the wisdom, the justice, and the power or might of

God (ST III, 1.1).” “By taking flesh, God did not lessen His majesty;

and in consequence did not lessen the reason for reverencing Him, which is

increased by the increase of knowledge of Him. But, on the contrary, inasmuch

as He wished to draw nigh to us by taking flesh, He greatly drew us to know Him

(ST III, 1.2).”

[22] John R. Betz, Christ the Logos

of Creation: An Essay in Analogical Metaphysics (Steubenville, OH: Emmaus

Academic, 2023).

[23] “Now the final perfection, which is

the end of the whole universe, is the perfect beatitude of the Saints at the

consummation of the world (ST I, 73.1).”

[24] These repeating patterns are

imprinted in Biblical revelation. The Jewish new year begins with death.

Passover (15th of Nisan) is when the seed dies (John 12:24). First

fruits are in spring. The nation climbs to Jerusalem in songs of ascents to

celebrate the feasts. Tabernacles follows the harvest (and judgment). Death and

resurrection are symbolized in baptism (Col 2:12) and communion, “proclaim[ing]

the Lord’s death until he comes” (our resurrection) (I Cor 11:26). Augustine

experiences this cycle in his ascent into God’s presence in prayer and his

descent to deliver the words he received (De doctrina christiana, IV,

xv, 32). The long ascent of the church on its pilgrimage through the age is

part of this picture.

[25] Scripture embeds this cyclicity in

the mirror structure of chiasma (ABB’A’). For example, Psalm 90, where Moses

compares God’s timeless transcendence with man’s evanescence, has a chiastic

structure.

[26] “Man has free-will: otherwise,

counsels, exhortations, commands, prohibitions, rewards, and punishments would

be in vain (ST I, 83.1).” “Wherever we have order among a number of

active powers, that power which regards the universal end moves the powers

which regard particular ends…The king [] who aims at the common good of the

whole kingdom, by his rule moves all the governors of cities, each of whom

rules over his own particular city…The will as agent moves all the powers of

the soul to their respective acts (ST I, 82.4).”

[27] In this framework, beliefs are

propositions about the current state of the world. Beliefs are drawn from

memory (past) and are constantly updated. Desires are propositions about

the future state of affairs the agent prefers. Intention commits the agent

to actions achieving these goals. Rao and Georgeff (Rao, 1998) formalize this

procedure using modal logic. Saul Kripke’s possible-world semantics assists the

authors in assessing belief-accessible (known), desire-accessible (sought), and

intent-accessible worlds (planned).

[28] “God knows all things; not only

things actual but also things possible to Him and creature; and since some of

these are future contingent to us, it follows that God knows future contingent

things…Contingent things are infallibly known by God, inasmuch as they are

subject to the divine sight in their presentiality; yet they are future

contingent things in relation to their own causes (ST I, 14.13).”

[29] “‘Man's way’ is said ‘not to be

his,’ in the execution of his choice, wherein he may be impeded, whether he

will or not. The choice itself, however, is in us, but presupposes the help of

God (ST I, 83.1).”